Important Note

Note: This page is updated (as of March 24, 2013), on my Chicago Cubs website. See Almost a Dynasty in the “Early Years” section of http://WrigleyIvy.com/.

“Any team can have a bad century,” is how Cubs broadcaster Jack Brickhouse occasionally shrugged off the team’s misfortunes. But over 100 years ago, fans reveled in the accomplishments of the Chicago North Siders. For example, shortstop Joe Tinker, second baseman Johnny Evers, and first baseman Frank Chance made up one of the most famous double-play combinations in the history of baseball. Their steady fielding and timely hitting helped the Cubs capture four National League pennants (1906-1908, 1910) and two World Series titles (1907–1908).

Of course, the other ballplayers contributed quite a bit as well. The fourth member of the Cubs famous infield was Harry Steinfeldt (a popular trivia question is “Who was the third baseman with Tinker, Evers and Chance”)? And Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown, who lost an index finger in a farming accident, was not only a renowned Cubs player, but he was also one of the most famous pitchers of all time. (From left to right in this 1907 photo is Steinfeldt, Tinker, Evers, and Chance.)

Of course, the other ballplayers contributed quite a bit as well. The fourth member of the Cubs famous infield was Harry Steinfeldt (a popular trivia question is “Who was the third baseman with Tinker, Evers and Chance”)? And Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown, who lost an index finger in a farming accident, was not only a renowned Cubs player, but he was also one of the most famous pitchers of all time. (From left to right in this 1907 photo is Steinfeldt, Tinker, Evers, and Chance.)

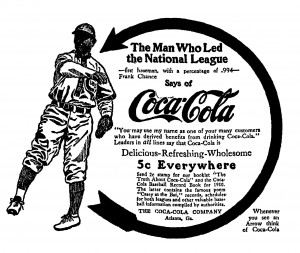

Frank Chance–who was often called “Husk” because of his husky physique or “The Peerless Leader”–became manager of the Cubs in 1905. He and his fellow ballplayers would be the first to acknowledge that tenacity and old-fashioned grit had much to do with the team’s good fortune.

And grit they certainly had. In 1934 Joe Tinker, long retired from baseball and living in Orlando, Florida, got to reminiscing with a St. Petersburg sports editor about his playing days and how the game–and the players–had softened up over the years. One of the stories jotted down by the sportswriter centered on fellow infielder Frank Chance: “It was one day after an especially hard-fought game which the Cubs lost after going into extra innings,” said Tinker. “Frank was fit to be tied. Mrs. Chance met him and tried to soothe him. She said: ‘Don’t take it so hard, Frank; you know, you still have me, even though you lost the game.’ To which Chance replied: ‘Yes, honey, I know, but there were a couple of times this afternoon when I would have traded you for a base hit.'”

And grit they certainly had. In 1934 Joe Tinker, long retired from baseball and living in Orlando, Florida, got to reminiscing with a St. Petersburg sports editor about his playing days and how the game–and the players–had softened up over the years. One of the stories jotted down by the sportswriter centered on fellow infielder Frank Chance: “It was one day after an especially hard-fought game which the Cubs lost after going into extra innings,” said Tinker. “Frank was fit to be tied. Mrs. Chance met him and tried to soothe him. She said: ‘Don’t take it so hard, Frank; you know, you still have me, even though you lost the game.’ To which Chance replied: ‘Yes, honey, I know, but there were a couple of times this afternoon when I would have traded you for a base hit.'”

The team’s archrivals in the early 1900s were John McGraw’s New York Giants, led by legendary pitcher Christy Mathewson. When a Chicago Daily News reporter asked Joe Tinker to recall his “greatest day” in baseball, the shortstop immediately replied that “you know it was against the Giants. I think that goes for every Cub who played for ‘Husk’ Chance in those years on Chicago’s West Side.” Warming to his subject, he added, “If you didn’t honestly and furiously hate the Giants, you weren’t a real Cub.”

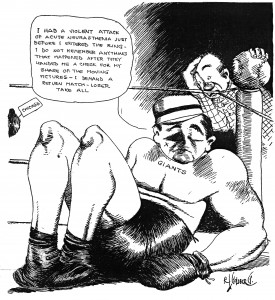

The Giants, their fans, and the New York press similarly relished the team’s confrontations with its Chicago nemesis, and the newspapers devoted much space to write-ups of the games. For example, this cartoon appeared in the July 12, 1910, issue of the New York Evening Mail, the day after the Cubs knocked out the Giants by the score of 4-2. (Click on cartoon, Coca-Cola ad, and above photo to enlarge.)

The Giants, their fans, and the New York press similarly relished the team’s confrontations with its Chicago nemesis, and the newspapers devoted much space to write-ups of the games. For example, this cartoon appeared in the July 12, 1910, issue of the New York Evening Mail, the day after the Cubs knocked out the Giants by the score of 4-2. (Click on cartoon, Coca-Cola ad, and above photo to enlarge.)

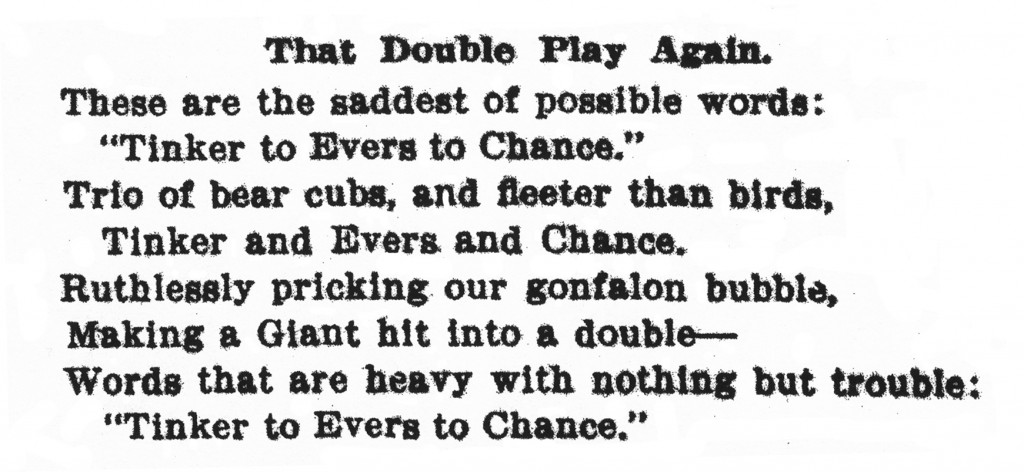

Although this cartoon has long been lost to history, the Evening Mail of July 12 featured something else that proved to be not nearly as transitory. Perhaps recalling a double play executed by the Cubs infield the day before, Chicago-born journalist Franklin P. Adams–and staunch Cubs fan–sat down and hastily scrawled a poem for his column, a verse that is best known today by its reprinted title, “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon.” Also called “Tinker to Evers to Chance,” it is the second-best-known baseball poem in America–close behind Ernest Thayer’s immortal “Casey at the Bat,” written in 1888.

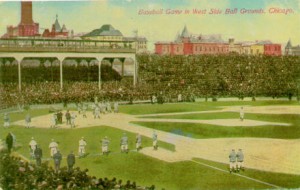

The Cubs’ storied World Series era took place not at Wrigley Field, but at the second West Side Park (also called the West Side Grounds), on the corner of Taylor, Polk, Wood, and Lincoln (now Wolcott) streets. The team played at the West Side Grounds from 1893 to 1915. The Cubs never won a World Series at Wrigley Field until 2016.

The Cubs’ storied World Series era took place not at Wrigley Field, but at the second West Side Park (also called the West Side Grounds), on the corner of Taylor, Polk, Wood, and Lincoln (now Wolcott) streets. The team played at the West Side Grounds from 1893 to 1915. The Cubs never won a World Series at Wrigley Field until 2016.

July 12, 2010, marked the 100th anniversary of Adams’s famous bit of doggerel. That year Tim Wiles, Director of Research at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and I discovered some new facts about the poem (including not only its original publication date but also its original title, “That Double Play Again”). We were thrilled, naturally, when the Chicago Tribune, Major League Baseball, and the Cubs blog Bleed Cubbie Blue covered our work on July 12. I later expanded my research in an article for Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture.

Here is the original version of Franklin P. Adams’s tribute to the Chicago Cubs’ infield, just as it appeared in the New York Evening Mail on July 12, 1910:

Note: This page is updated (as of March 24, 2013), on my Chicago Cubs website. See Almost a Dynasty in the “Early Years” section of http://WrigleyIvy.com/.